I’ve been making Neapolitan-style pizza at home for a few years now, first using the cast-iron skillet method, then a baking steel, and, most recently and successfully, an Ooni Volt 12. I often use 00 flour for Neapolitan-style pizza. I knew it provided the best texture and flavor but did not completely understand what made 00 flour unique. My confusion came from the many websites that only provide half the 00 flour story. However, I recently discovered the full Italian 00 flour story — what sets it apart from other flours. Since I struggled to find a reputable online resource that fully explains what Italian tipo 00 flour is, I decided to explain it here.

The largest source of confusion around 00 flour for me came from trying to apply U.S. flour classifications to Italian flours. It turns out that many countries have their own flour classification systems, often differing widely from the U.S. standards. So to understand Italian flour, if you’re a used to using U.S. flours, you need to first recognize how the U.S. labels flour and then how that system differs from standards used in Italy and other countries.

U.S. Flour Classification Systems

In the U.S. flour producers classify their products based on wheat type (soft or hard) and protein content and label flours according to their purposes with the following five types appearing most frequently: cake flour, all-purpose flour, pastry flour, bread flour, and high-gluten flour. Unfortunately, brands base these names on their own opinions of what works best for each application, which means that the flours produced by each brand have variations even though they have the same name. For example, all purpose flour from King Arthur has a protein content of 11.7%, while Gold Medal’s all purpose flour has a protein content of 10.5% — over a 1% difference, enough to make a significant difference in the resulting dough. Some brands, like Pilsbury and Hodgson Mill don’t even have an exact protein content, aiming for a range instead. If you’re using U.S. flour for making pizza, you will most likely be using bread, all-purpose, high-gluten (for New York style), or some combination of those flours. Further, in the U.S. there are no gradations between white and whole wheat flour — you either have flour with almost all the wheat bran and germ sifted out (white flour) or whole wheat, with nothing removed. And, although pastry flour is usually ground to a finer texture than other U.S. flours, there is no widely used U.S. system to grade the fineness of the grind. (In this paragraph, I’m speaking broadly, focusing on commonly available flours — the U.S. does have artisanal producers that follow more European standards.)

Italian Flour Classifications

In Italy, and several other European countries, ash content is an important component of how flour is classified. Ash content allows for gradations between white flour and whole wheat and is calculated by measuring the ash that remains after testers burn a portion of flour in a lab. The minerals in a wheat berry are contained primarily in the bran and endosperm and, because the minerals don’t burn easily, more ash indicates more of the endosperm and bran and a flour closer to what U.S. bakers call whole wheat.

The 1st Meaning of 00: Ash Content

In Italy, ash content is the first of two things indicated by the 00 in Tipo 00 flour. 00 flours have the lowest ash content, which means they are the whitest flours you can get in Italy. Next, with a slightly higher ash content, is Tipo 0, then, Tipo 1, and Tipo 2, which is nearly whole wheat flour by U.S. standards. (I believe that whole wheat flour in Italy is called “farina di grano integrale” (“whole wheat” in English).)

The Second Meaning of 00: Grind Fineness

The second characteristic indicated by the 00 is the fineness of the grind. Tipo 00 is the most finely ground flour in the Italian classification system. For a while, I only understood this part of the 00 classification because it is the one easiest for U.S. bakers to comprehend and the most common characteristic of 00 flours cited on U.S. websites. Daniel Leader’s book, Living Bread, finally explained the meaning of 00 to me, and, if you want to learn more about flour, I highly recommend the book.

What Italian’s Use Instead of Protein Percentage

What about the U.S. guiding light, protein content? Does 00 indicate something about the amount of protein in the flour? Nope. In Italy and other European countries, protein content means less than it does in the U.S. and for good reason. It turns out that protein content is only a rough approximation for how elastic a dough made from the flour will be — higher protein flours usually produce more elastic doughs that tear less easily but are also less extensible (i.e. harder to stretch when shaping a pizza), while lower protein doughs tend to have less elasticity and stretch more easily. In reality, a lot more than protein content determine how elastic a dough the flour will produce. So, in Italy, rather than relying on the unreliable protein content to indicate the how elastic a dough a flour will produce, Italian flour makers actually have the elasticity of their flours tested via an alvégraph assessment. In the assessment, technicians mix a dough, then make a dough bubble, blowing air into it until the dough bubble pops. The larger the bubble gets before bursting, the higher its rating on the scale. Flour makers report the results of the alvégraph test by W value, with a higher value indicating a flour that will produce a more elastic dough. W values below 120 indicate low-quality flours that wouldn’t work for pizza. A flour with a W value over 300 is on the high end of the spectrum. According to an Italian website archived by Wikipedia and translated by Google, the following W values and protein percentages usually align

| W Value | Protein % |

| 90-130 | 9-10.5% |

| 170-200 | 10.5-11.5% |

| 220-240 | 12-12.5% |

| 300-310 | 13% |

| 340-400 | 13.5-15% |

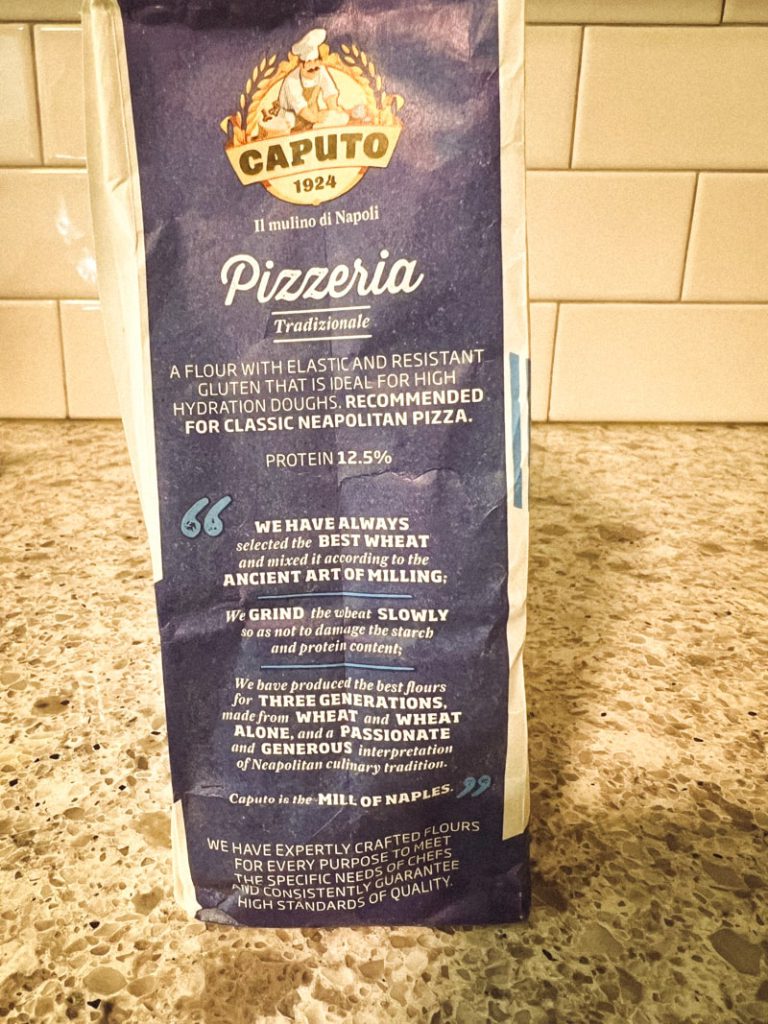

Interestingly, it appears that Caputo, one of the largest Italian flour producers that distributes in the U.S., has removed the W value from the packaging of the flours they sell in the America. My bag of Caputo blue lists the protein at 12.5% but doesn’t have a W value anywhere. (While the bag has some token Italian, the dominance of English indicates that this is not the same packaging used in Italy.)

What Does This Mean & the Best Substitute for 00 Flour

What does all this mean for pizza makers in the U.S.? In my opinion, the more nuanced Italian and European flour classifications would allow for more predictability when making pizza — if you know the ash content, fineness of the grind, and W value, you will have a very good idea what type of pizza dough a flour will produce. In the U.S., you’ll need to experiment a bit more to find out exactly how flours perform. Understanding the differences also makes it easier to substitute 00 flour with more commonly available flours. The W value will most likely be unexpectedly low relative to protein content if low quality wheat is used. So, if we assume that Caputo produces high-quality Italian flours and King Aruthur produces high-quality American flours, then we should surmise that flours with similar protein contents will perform similarly across both brands. I have confirmed this by making Neapolitan-style pizzas in my Ooni Volt with both Caputo blue (protein content 12.5%) and King Arthur bread flour (protein content 12.7%). The pizzas came out similar. In the image at the start of this section, the one on the left is made with Caputo blue and the one on the right with King Arthur bread flour. The most noticeable difference was that the Caputo pizzas had a more tender crust, while the King Arthur ones had more chew. I think this is probably because of the fine grind used in the Caputo, which is a Tipo 00 flour. If you make pizza a lot or eat at Neapolitan pizzerias regularly, you’ll likely notice the difference, but a good portion of the people you make your pizzas for probably will not. So, if you don’t have access to a good 00 flour and want to make Neapolitan-style pizza, I’d recommend going with King Arthur bread flour.